Story

Our STORY – Our Hungarian and Scottish connections

The Sárvári family from the Lake Balaton region in Hungary started breeding potatoes for high resistance to late-blight disease over 40 years ago. The late Dr Sárvári was director of Keszthely Research Institute (now University of Pannonia Georgikon, Faculty of Agriculture, Potato Research Centre). His Soviet bosses wanted a hardy strain of potatoes for growing across the USSR which would survive the ravages of climate and disease and that was not dependent on expensive chemical inputs.

Research Institute (now University of Pannonia Georgikon, Faculty of Agriculture, Potato Research Centre). His Soviet bosses wanted a hardy strain of potatoes for growing across the USSR which would survive the ravages of climate and disease and that was not dependent on expensive chemical inputs.

Using South American and Mexican wild potato material from the Vavilov collection, genes conferring resistance to common viruses (including PVX, PVY, PLRV) were soon bred into his stocks. Resistance to late-blight disease took a little longer but eventually, exceptionally high resistance was achieved. Dr Sárvári and his wife left the Potato Research Centre and continued breeding privately at their home.

Using South American and Mexican wild potato material from the Vavilov collection, genes conferring resistance to common viruses (including PVX, PVY, PLRV) were soon bred into his stocks. Resistance to late-blight disease took a little longer but eventually, exceptionally high resistance was achieved. Dr Sárvári and his wife left the Potato Research Centre and continued breeding privately at their home.

While visiting potato trials in Romania, veteran, Scottish, seed-potato grower, Adam Anderson, observed some  plants from Hungary surviving in a devastated field of blighted potatoes. The hunt was on and Adam tracked the plants down to the Sárvári family in 1994. A company was soon formed to support the breeders, with Adam, partner William Wedderspoon and the Danish Seed potato group, Danespo. The company built a small breeding station near the Sárvári family home in the village of Zirc, near Veszprém and Lake Balaton. The laboratory, greenhouse, potato store and experimental kitchen were surrounded by trial fields. Unfortunately, Dr Sárvári, Snr, died in 1995 before any Sárpo potatoes had been commercialized.

plants from Hungary surviving in a devastated field of blighted potatoes. The hunt was on and Adam tracked the plants down to the Sárvári family in 1994. A company was soon formed to support the breeders, with Adam, partner William Wedderspoon and the Danish Seed potato group, Danespo. The company built a small breeding station near the Sárvári family home in the village of Zirc, near Veszprém and Lake Balaton. The laboratory, greenhouse, potato store and experimental kitchen were surrounded by trial fields. Unfortunately, Dr Sárvári, Snr, died in 1995 before any Sárpo potatoes had been commercialized.

The good work continued with sons Dr István Sárvári Jnr., Dr Balázs Sárvári and their mother, Dr M. Sárvári. Promising new clones were sent to Adam in Scotland who had them grown in a trial

with the world’s best resistant varieties in Ayrshire. David Shaw visited the trial and was impressed by the top performance of the Hungarian clones. Adam, William, David and Murdo McKenzie (New Park Management) set up the Trust in 2002. The Trust was sited near Bangor, North Wales, where David had been researching late-blight disease and blight resistant varieties since he arrived at Bangor University in 1967. The story goes that in the early days of the Trust, David was paid in rather large bottles of malt whisky from a barrel in Adam’s basement.

The first variety to be Nationally Listed in 2002 was Sarpo Mira, a clone with outstanding resistance. This was followed shortly after by Axona, another maincrop clone with good flavour.

Simon White joined David in 2004 and took over the management of blight trials, selection of newer seedlings and the multiplication of seed of established varieties in preparation for marketing. This allowed selection of more seedlings with commercial potential to extend the range of blight-resistant Sarpo varieties to include other skin colours, earlier maturities and waxy/salad types. Successful National Listing of these clones extend the Sarpo family of varieties to six in all.

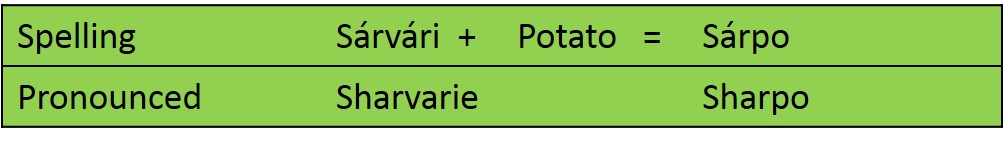

Just in case you’ve heard two versions of how Sarpo or Sarvari is pronounced … here is chapter and verse

How we take a new variety to market

Having selected a promising seedling with the traits that we want, it takes some time, effort and money before it can be marketed.

Firstly – it needs to be fully assessed for its strengths and weaknesses by government laboratories, in this case SASA (Science & Advice for Scottish Agriculture). This takes two years of tests in the laboratory and in the field (expensive) and if the strengths outweigh the weaknesses, SASA will award the new variety a place on the National List of varieties that can be legally sold in UK.

Secondly – the potato is established in tissue culture by SASA. Small, germ-free plantlets are grown in a honey jar of nutrient agar. These are tested for viruses and any found have to be eliminated using heat and chemical treatments. Pure cultures are then kept growing slowly in the lab like this, indefinitely – expensive!

Thirdly – germfree microplants from SASA are used to make rooted cuttings and these are weaned into sterile compost in a special government-approved greenhouse. These plants grow on to form the first crop of small tubers – minitubers (expensive).

Fourthly – minitubers delivered to SRT are planted in a field, isolated from other potatoes and while growing, the crop is examined by APHA (Animal and Plant Health Agency) inspectors and given a certificate if the crop is pure (not mixed with other varieties) and healthy (free of all pests and diseases). The seed from this kind of crop is known as PreBasic. This seed can be multiplied again and certified PreBasic (expensive).

The seed is passed to Sarpo Potatoes Ltd to have it grown and certified over several seasons until there is enough to sell. New regulations limit the multiplication of any stock to nine years but only seven years in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Cumbria and Northumberland. After that, the stock cannot be replanted to produce seed. Instead, a more recent stock grown from minitubers must be established.